Climate, whether it is changing too fast to suit you or is too slow showing off its really cool stuff, is an important part of a story.

The nastier the better if you want to churn up some deviant behavior. Nothing like a blizzard or flood to turn a tough time into a really bad day.

The best part of winter is that it happens partly around the Christmas holidays, which can create issues with people who are, say ... in need of government help.

"The director is out of town until the fifth of January. Is there someone else who can help you?"

"The damned dam is about to collapse and I NEED the director's permission to do ... um ... who else can help me?"

Conversely, summer heat and humidity are nice tools for driving rural stories. (Hot town, summer in the city.)

So you get that sort of option when creating dramatic tension with weather as a primary component of the yarn you want to spin.

Volcanoes, earthquakes, tidal waves are all interesting and powerful devices, but frequently they are major events that create settings. It's less likely you can write effectively about a volcano since I'd wager you have never experienced one. The last tidal wave to visit Indiana was ... yeah, you got no idea about that either, do you?

A gloomy winter helps develop characters. Unless you live in San Diego, you should be able to communicate that.

Pay some attention to the weather when starting a novel, remembering that today's blizzard is tomorrow's lost dog in the snow. Weather might not be the primary driver of the story but it adds sidebars and makes the routine somewhat unpredictable.

And the real weather you experience has affected your emotional outlook on life. Prepare to understand yourself.

Tuesday, March 13, 2018

Friday, March 9, 2018

Six of one ...

Lucky for me, most of what I read is bereft of cliches. I try to avoid sports reporting, political writing in conjunction with the stock market and almost anything dealing with arguments between birth control users and people who think Viagra is birth control.

That leaves me with real writing. Back in my years, I fought gamely against lazy headline writers and reporters who thought the clever turn of a phrase was unique. Borrowing from last year's issue doesn't make it anything but tedious.

In my attempts to create solid narrative, I find myself noticing what I write, wondering if the cliche (or overdone phrase) is useful or if it's a roadblock to a better verb,

I like verbs.

Naturally, a quippy turn of a phrase when least expected can create some interesting literary abrasion. It can help ease the tedium.

So long as it isn't a crutch. Depending on the cliche to tell a story suggests something is missing, that mainly being depth in the development of the character.

I think characters speak in cliches, but they're not likely advancing the story if they do much of it and it suggests strongly they aren't very interesting.

By and large, I avoid cliches like the plague.

That leaves me with real writing. Back in my years, I fought gamely against lazy headline writers and reporters who thought the clever turn of a phrase was unique. Borrowing from last year's issue doesn't make it anything but tedious.

In my attempts to create solid narrative, I find myself noticing what I write, wondering if the cliche (or overdone phrase) is useful or if it's a roadblock to a better verb,

I like verbs.

Naturally, a quippy turn of a phrase when least expected can create some interesting literary abrasion. It can help ease the tedium.

So long as it isn't a crutch. Depending on the cliche to tell a story suggests something is missing, that mainly being depth in the development of the character.

I think characters speak in cliches, but they're not likely advancing the story if they do much of it and it suggests strongly they aren't very interesting.

By and large, I avoid cliches like the plague.

Thursday, March 1, 2018

Ben Hur: more than a movie

How do you describe setting?

I think the secret lies in some of the older writing, meaning ... from the 19th century. It's important to understand that writers from the days before television or even cinema had few visual images of the worlds they described. Unless they'd been there -- and some of the more prominent writers of the day did travel a lot -- they had only other books, maps and acquaintances as reference. Diaries and journals helped. Photographs were less useful.

One can see a mountain and visualize life on it. To visualize it and describe it, two topics. The reader almost certainly had not seen this mountain. It's also important to remember that extensive travel was, depending on the area, not easily achieved by the masses.

In fact, most people of the time could scarcely afford the book, let alone the dream of experiencing what it described.

Some of that deals with verbs. They make birds fly, people sing and jump and dance. They make bears roar and trains rumble. I still don't know how many ways there are (were) to describe what people do when they are standing around, talking to each other.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.

But you are there with this paragraph.

When the dromedary lifted itself out of the last break of the wady, the traveler had passed the boundary of El Belka, the ancient Ammon. It was morning-time. Before him was the sun, half curtained in fleecy mist; before him also spread the desert; not the realm of drifting sands, which was farther on, but the region where the herbage began to dwarf; where the surface is strewn with boulders of granite, and gray and brown stones, interspersed with languishing acacias and tufts of camel-grass. The oak, bramble, and arbutus lay behind, as if they had come to a line, looked over into the well-less waste and crouched with fear.

Modern writers might describe this scene in much the same way, but the cadence of the writing will have changed. That's natural. It's what makes the craft so appealing.

Wallace was a master at painting a scene. Again, the language and cadence of the day:

At this age the apartment alluded to would be termed a saloon. It was quite spacious, floored with polished marble slabs, and lighted in the day by skylights in which colored mica served as glass. The walls were broken by Atlantes, no two of which were alike, but all supporting a cornice wrought with arabesques exceedingly intricate in form, and more elegant on account of superadditions of color -- blue, green, Tyrian purple, and gold. Around the room ran a continuous divan of Indian silks and wool of Cashmere. The furniture consisted of tables and stools of Egyptian patterns grotesquely carved.

Setting, and what makes it important. Wallace nails it here:

His shoes were brought him, and in a few minutes Ben-Hur sallied out to find the fair Egyptian. The shadow of the mountains was creeping over the Orchard of Palms in advance of night. Afar through the trees came the tinkling of sheep bells, the lowing of cattle, and the voices of the herdsmen bringing their charges home. Life at the Orchard, it should be remembered, was in all respects as pastoral as life on the scantier meadows of the desert.

If you only saw the movie, you missed the best part of this story.

I think the secret lies in some of the older writing, meaning ... from the 19th century. It's important to understand that writers from the days before television or even cinema had few visual images of the worlds they described. Unless they'd been there -- and some of the more prominent writers of the day did travel a lot -- they had only other books, maps and acquaintances as reference. Diaries and journals helped. Photographs were less useful.

One can see a mountain and visualize life on it. To visualize it and describe it, two topics. The reader almost certainly had not seen this mountain. It's also important to remember that extensive travel was, depending on the area, not easily achieved by the masses.

In fact, most people of the time could scarcely afford the book, let alone the dream of experiencing what it described.

Some of that deals with verbs. They make birds fly, people sing and jump and dance. They make bears roar and trains rumble. I still don't know how many ways there are (were) to describe what people do when they are standing around, talking to each other.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.But you are there with this paragraph.

When the dromedary lifted itself out of the last break of the wady, the traveler had passed the boundary of El Belka, the ancient Ammon. It was morning-time. Before him was the sun, half curtained in fleecy mist; before him also spread the desert; not the realm of drifting sands, which was farther on, but the region where the herbage began to dwarf; where the surface is strewn with boulders of granite, and gray and brown stones, interspersed with languishing acacias and tufts of camel-grass. The oak, bramble, and arbutus lay behind, as if they had come to a line, looked over into the well-less waste and crouched with fear.

Modern writers might describe this scene in much the same way, but the cadence of the writing will have changed. That's natural. It's what makes the craft so appealing.

Wallace was a master at painting a scene. Again, the language and cadence of the day:

At this age the apartment alluded to would be termed a saloon. It was quite spacious, floored with polished marble slabs, and lighted in the day by skylights in which colored mica served as glass. The walls were broken by Atlantes, no two of which were alike, but all supporting a cornice wrought with arabesques exceedingly intricate in form, and more elegant on account of superadditions of color -- blue, green, Tyrian purple, and gold. Around the room ran a continuous divan of Indian silks and wool of Cashmere. The furniture consisted of tables and stools of Egyptian patterns grotesquely carved.

Setting, and what makes it important. Wallace nails it here:

His shoes were brought him, and in a few minutes Ben-Hur sallied out to find the fair Egyptian. The shadow of the mountains was creeping over the Orchard of Palms in advance of night. Afar through the trees came the tinkling of sheep bells, the lowing of cattle, and the voices of the herdsmen bringing their charges home. Life at the Orchard, it should be remembered, was in all respects as pastoral as life on the scantier meadows of the desert.

If you only saw the movie, you missed the best part of this story.

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

Verbs that aren't

A billion years ago, a writing coach told me that if I wanted to succeed at the craft on any level, that I should avoid the following:

IS

ARE

WAS

WERE

The four weakest verbs in the English language.

The first thought was (is) that there are (is) not much way to avoid that.

Well, yes there is (was).

The trick, you see, is (was) to use verbs that sing, that drive the story. The better the verb, the better the description. In a sense, the way to make better sentences is (was) to use verbs that do something.

There is a tree in the yard.

The tree in the yard stood like a gigantic monument to time.

It is (was) still a tree, but we have some idea of its dimensions, once we realize that the tree stands in the yard, which I suppose is (was) different from it lying on its side.

Powerful verbs help a writer because powerful verbs create a need to produce better descriptions. Verbs move our lives.

Try it sometime. Take your average sentence, even one so benign as "I am talking on the phone" and turn it into something far more dramatic.

The best authors seldom rely on is-are-was-were for description.

There are (were) times when those verbs are (were) helpful.

Try to think of something better.

IS

ARE

WAS

WERE

The four weakest verbs in the English language.

The first thought was (is) that there are (is) not much way to avoid that.

Well, yes there is (was).

The trick, you see, is (was) to use verbs that sing, that drive the story. The better the verb, the better the description. In a sense, the way to make better sentences is (was) to use verbs that do something.

There is a tree in the yard.

The tree in the yard stood like a gigantic monument to time.

It is (was) still a tree, but we have some idea of its dimensions, once we realize that the tree stands in the yard, which I suppose is (was) different from it lying on its side.

Powerful verbs help a writer because powerful verbs create a need to produce better descriptions. Verbs move our lives.

Try it sometime. Take your average sentence, even one so benign as "I am talking on the phone" and turn it into something far more dramatic.

The best authors seldom rely on is-are-was-were for description.

There are (were) times when those verbs are (were) helpful.

Try to think of something better.

Old as dirt Part II

I have no compelling reason to include a second or even a third component to the principle that literary life lies only in the depths of our past.

A search of century-old newspapers produces all of that; modern newspapers and other publications do the same thing. The major difference is history is sealed. The present has yet to become the history, and it's far more difficult to pin down.

Let's just say: Reading about the past is as much about what did not happen as what did happen. Everyone has seen the past; almost nobody has seen the future and it's likely I don't agree with your vision of it.

That's important when considering a story written in contemporary times, one that leads inevitably to a focus on the what-ifs that manifest as the future.

The weapons of war in 1918 have been defined, and we know what impact they had. What the Pentagon is dreaming up today lives in our imagination. We simply do NOT need to re-create a light saber or focus-based ray gun for future killing. It's been done. When all else fails, produce a race of super-smart people and you can invent any damned thing you want.

The reality is machines aren't made that way. They are tools that are modified and enhanced as the result of other inventions.

New stuff is being invented every day.

Which is sort of the point of the old newspapers. They're chock-full of tidbits about flying aerocraft, machines that milk cows, medicines, sewage treatment plants, long-lasting electric light bulbs.

And ruts in the road, hogs on the train tracks, people dying of typhoid.

Simply put, we can approach any event from two directions, from now looking back and from now looking forward. It's the 'from now' part that flattens it out.

One approach isn't better than the other.

It's been said that any three people can come together over the carcass of a skunk in the middle of a county road and become the framework of a novel.

The century-old newspapers -- the better ones are the small-town weeklies -- are simply loaded with characters, stories, anecdotes and events. These stories are the front door to the future.

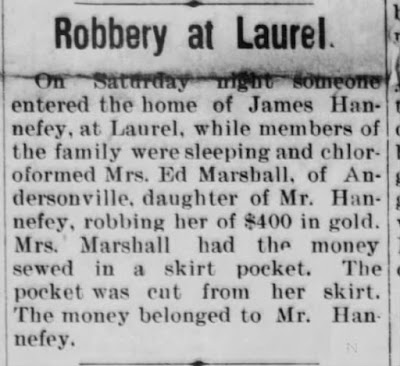

Consider the attached clip.

Chloroform? Was that a common product in 1917? Seems like an inside job if the robber knew where to look. Why would somebody have that much money sewn into a pocket. Gold? This is rural Indiana.

Sounds like a pretty damned interesting mystery novel to me. You could even turn this into a romance.

Just ordinary stuff in the average weekly newspaper.

This one from 1920:

Everything about this real event sounds and smells like "To Kill A Mockingbird." If you can't write a story about this event, the people who would be central to it and its potential outcome, take time to sniff the coffee. "Believed to be negroes ..." is focal. Looks a bit like Ernest is tryin' to pin a crime on some imaginary evil people. (Probably owed somebody money.)

In short:

Get your head out of the future and stop pretending that everything that isn't real is somehow better.

A search of century-old newspapers produces all of that; modern newspapers and other publications do the same thing. The major difference is history is sealed. The present has yet to become the history, and it's far more difficult to pin down.

Let's just say: Reading about the past is as much about what did not happen as what did happen. Everyone has seen the past; almost nobody has seen the future and it's likely I don't agree with your vision of it.

That's important when considering a story written in contemporary times, one that leads inevitably to a focus on the what-ifs that manifest as the future.

The weapons of war in 1918 have been defined, and we know what impact they had. What the Pentagon is dreaming up today lives in our imagination. We simply do NOT need to re-create a light saber or focus-based ray gun for future killing. It's been done. When all else fails, produce a race of super-smart people and you can invent any damned thing you want.

The reality is machines aren't made that way. They are tools that are modified and enhanced as the result of other inventions.

New stuff is being invented every day.

Which is sort of the point of the old newspapers. They're chock-full of tidbits about flying aerocraft, machines that milk cows, medicines, sewage treatment plants, long-lasting electric light bulbs.

And ruts in the road, hogs on the train tracks, people dying of typhoid.

Simply put, we can approach any event from two directions, from now looking back and from now looking forward. It's the 'from now' part that flattens it out.

One approach isn't better than the other.

It's been said that any three people can come together over the carcass of a skunk in the middle of a county road and become the framework of a novel.

The century-old newspapers -- the better ones are the small-town weeklies -- are simply loaded with characters, stories, anecdotes and events. These stories are the front door to the future.

Consider the attached clip.

Chloroform? Was that a common product in 1917? Seems like an inside job if the robber knew where to look. Why would somebody have that much money sewn into a pocket. Gold? This is rural Indiana.

Sounds like a pretty damned interesting mystery novel to me. You could even turn this into a romance.

Just ordinary stuff in the average weekly newspaper.

This one from 1920:

Everything about this real event sounds and smells like "To Kill A Mockingbird." If you can't write a story about this event, the people who would be central to it and its potential outcome, take time to sniff the coffee. "Believed to be negroes ..." is focal. Looks a bit like Ernest is tryin' to pin a crime on some imaginary evil people. (Probably owed somebody money.)

In short:

Get your head out of the future and stop pretending that everything that isn't real is somehow better.

Monday, February 26, 2018

Old as dirt, Part I

Part of my love of writing connects to the writer as much as the subject matter. Nothing illustrates this more than weekly newspapers from a century or more ago.

To preface, the men (and there were a few women, though usually unnamed) who published these newspapers were not journalists. They had no training in the craft. Their grammar was at times suspect and their opinions were scarcely contained on the op-ed page.

If they thought something was a big deal, it was a big deal. Where it appeared in the paper had almost nothing to do with that. That was called production. Hot metal. Galleys. Turtles. You will never experience that.

I came across a lot of fun stuff in 2015 when I did a bicentennial blog. Since then, I have found my love for old newspapers to be nothing short of zealous.

It's about the adjective.

The point of view.

The point of view.

It's about what we were told, not what we know.

It's about life.

The old newspapers from a century ago are the front door to the future. No writer of serious merit ought to overlook them. The idea well is nearly bottomless. The articles are fascinating on a lot of levels, the main one being a presumption that being odd, sick, alone, poor or awesome was just ... well, everybody's business.

To preface, the men (and there were a few women, though usually unnamed) who published these newspapers were not journalists. They had no training in the craft. Their grammar was at times suspect and their opinions were scarcely contained on the op-ed page.

If they thought something was a big deal, it was a big deal. Where it appeared in the paper had almost nothing to do with that. That was called production. Hot metal. Galleys. Turtles. You will never experience that.

I came across a lot of fun stuff in 2015 when I did a bicentennial blog. Since then, I have found my love for old newspapers to be nothing short of zealous.

It's about the adjective.

The point of view.

The point of view.It's about what we were told, not what we know.

It's about life.

The old newspapers from a century ago are the front door to the future. No writer of serious merit ought to overlook them. The idea well is nearly bottomless. The articles are fascinating on a lot of levels, the main one being a presumption that being odd, sick, alone, poor or awesome was just ... well, everybody's business.

World building Part III

The first part of any story I read that centers around world building is that the premise is predictable:

It's US against THEM, WE are the underdog and THEY are truly evil with almost unlimited resources.

All WE need to do is outrun the hare and collect the golden chalice from the grateful king at the grand ceremony. Of course, the race is fixed.

I'd be OK with that premise if I knew a real good reason why THEY are always evil and WE are always the underdog. Naturally, it's about control. It's also about human behavior, which seems contradictory in the sense that the world we're building is anything but that.

The best part of this sort of story is that we can imply that the evil ones, or THEM, are either part machine or mostly heartless and soul-barren beast. That allows US to get credit for slaying THEM for the greater good with impunity.

Hell, even on Earth, there are those who think the cockroach is God's creature. Read that sentence again, please.

Most world building comes from the Saturday morning cartoon, a genre that fully exploits our right and duty to murder anything that represents THEM, because as we know it, THEY ain't human.

And THEY want to subjugate US for reasons that just make sense.

Stop me if I ever try to write this story.

It's US against THEM, WE are the underdog and THEY are truly evil with almost unlimited resources.

All WE need to do is outrun the hare and collect the golden chalice from the grateful king at the grand ceremony. Of course, the race is fixed.

I'd be OK with that premise if I knew a real good reason why THEY are always evil and WE are always the underdog. Naturally, it's about control. It's also about human behavior, which seems contradictory in the sense that the world we're building is anything but that.

The best part of this sort of story is that we can imply that the evil ones, or THEM, are either part machine or mostly heartless and soul-barren beast. That allows US to get credit for slaying THEM for the greater good with impunity.

Hell, even on Earth, there are those who think the cockroach is God's creature. Read that sentence again, please.

Most world building comes from the Saturday morning cartoon, a genre that fully exploits our right and duty to murder anything that represents THEM, because as we know it, THEY ain't human.

And THEY want to subjugate US for reasons that just make sense.

Stop me if I ever try to write this story.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)