Most writers will assert that inspiration comes from the search for the "human condition" and how it drives ... um, people. Most writers abide in the First World, are educated enough to carry on a decent* conversation and are generally aware of life inside a social realm.

It's the social realm where we conveniently fit because we are attuned to the agenda. The agenda that tells us that intolerance is never acceptable. The agenda is known to change without notice, creating some awkward moments. I mean, I am OK with LGBT, but I don't know about the other 9 letters that come after that.

I am also intolerant of people who think I have no right to have opinions, which usually are pinned to my level of tolerance on any given matter. Gregorian chants suck, OK?

The First World is the perfect place to nurture diverse ideas. If you live in some other world, the options are different. Not better, just different. Cut down a tree to feed your family and we'll embargo your country for letting a poor farmer destroy the rain forest.

Understanding the "human condition" means having virtually zero idea what true poverty includes and why it won't ever go away. That doesn't mean not caring about it or not fixing the parts that aren't too deeply embedded in the problem. If you don't understand the problem, refrain from evaluating it from your pulpit.

Everybody is prejudiced, naturally.

Everyone is a bigot, intentionally.

We're all biased. That's not a sin, and it isn't a sin to write as though it's not. Everybody hates the bad guy -- even if he does have some socially redeeming value -- and we all abhor the evil creature from Xaptrahonia who comes to Earth to eat all the females. Yeah, that's evil ... but if this creature doesn't get his nourishment, he dies. Do we care? Well, if we care about all things, then the Xaptrahonian culture should be pretty precious to us.

In the same way a nest of ground hornets serves a natural purpose anywhere except near your back porch.

Hell, even Hitler liked dogs.

You gotta hate something if you want to bond with people who can make you feel good about yourself. If you are alone, you will never experience the human condition, which has finally lost its quote marks.

As writers, we can all perch high above it and pretend we have this insight, insight brought about by our ability to spell, punctuate and make it all grow into sentences, paragraphs and pamphlets.

We don't need to be so arrogant about it.

* As defined by Facebook.

Friday, September 7, 2018

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Summer of the Disco Tent

I let this blog slide for a few months while my pinkie stopped being numb. It's still numb, but the malady has spread to areas above the neckline.

Summer has slithered past, promising one thing, delivering it without comment and preparing to step aside for autumn.

Autumn is an especially nice time to be a writer, or even a person who sees the world through what might be a writer's eyes. The days are shorter, the shadows longer, and the breeze threatens to become a howling wind right about the time we decide to carve triangles into the front of an orange squash.

Turning it and its habitat into an eerie corral of creatures.

That's the problem with the whole story. It's always the same creatures. People only know the creatures they've experienced and most of them are dreadfully uninteresting.

The ones that matter are inside the mind. Scary stuff, that.

For the moment, the scratching, growling, snarling thing on the other side of the tree is content. In another couple of months, it will emerge, turning autumn into a graveyard of fear and anxiety.

That should be fun. And the mums will be in full bloom.

I had the opportunity to take part in an essay contest that described life for a solitary person on a deserted island, filled with horror. I didn't win. I wanted to win. Honestly, I don't know how a deserted island could contain any horror that didn't contribute to it being deserted in the first place. But anyway, I decided to show up there and get the scoop.

There is a germ of a story emerging. Let me think it over and get back to you.

Summer has slithered past, promising one thing, delivering it without comment and preparing to step aside for autumn.

Autumn is an especially nice time to be a writer, or even a person who sees the world through what might be a writer's eyes. The days are shorter, the shadows longer, and the breeze threatens to become a howling wind right about the time we decide to carve triangles into the front of an orange squash.

Turning it and its habitat into an eerie corral of creatures.

That's the problem with the whole story. It's always the same creatures. People only know the creatures they've experienced and most of them are dreadfully uninteresting.

The ones that matter are inside the mind. Scary stuff, that.

For the moment, the scratching, growling, snarling thing on the other side of the tree is content. In another couple of months, it will emerge, turning autumn into a graveyard of fear and anxiety.

That should be fun. And the mums will be in full bloom.

I had the opportunity to take part in an essay contest that described life for a solitary person on a deserted island, filled with horror. I didn't win. I wanted to win. Honestly, I don't know how a deserted island could contain any horror that didn't contribute to it being deserted in the first place. But anyway, I decided to show up there and get the scoop.

There is a germ of a story emerging. Let me think it over and get back to you.

Thursday, April 26, 2018

A winning idea

I spent the last few weeks not writing, not because I had no interest in it but because the world got more interesting.

As we used to say in market research, "IN WHAT WAY?"

The groundhog emerged from hibernation, which is always a treat. I really don't think it needs to get more interesting than that. It's not that he emerged, it's that nobody seems to know where he emerged from.

But my typewriter fingers are itchy lately and the inevitable 'gee, it's too nice to stay inside and write' is probably gonna do me in. Maybe not.

I wrote a raunchy 240-page novel a dozen years ago about a guy who wins the lottery and runs into a whole series of miscreants, thieves, buggers and deviants on his way to nowhere sensible. I liked the book, some of the characters and the plot.

I think I might try that plot idea again with a different motive in mind. I always wondered what would become of me if I ever won the lottery. Most of us wonder that. I think it's odd that we all say we wouldn't change. In real life, you would. In my book, I don't have to. The fun part of creating characters based on yourself is that you can make it anything you like.

See, what doubles as writing or story-telling is a matter of taking the mundane, adding two somewhat interesting people, have them do something and off you go. The guy winning the lottery has many more options in such a story.

I like options. You meet the strangest people on the way to the park.

Winning the lottery is not mundane but you still need to deal with groundhogs, who do not need the money.

As we used to say in market research, "IN WHAT WAY?"

The groundhog emerged from hibernation, which is always a treat. I really don't think it needs to get more interesting than that. It's not that he emerged, it's that nobody seems to know where he emerged from.

But my typewriter fingers are itchy lately and the inevitable 'gee, it's too nice to stay inside and write' is probably gonna do me in. Maybe not.

I wrote a raunchy 240-page novel a dozen years ago about a guy who wins the lottery and runs into a whole series of miscreants, thieves, buggers and deviants on his way to nowhere sensible. I liked the book, some of the characters and the plot.

I think I might try that plot idea again with a different motive in mind. I always wondered what would become of me if I ever won the lottery. Most of us wonder that. I think it's odd that we all say we wouldn't change. In real life, you would. In my book, I don't have to. The fun part of creating characters based on yourself is that you can make it anything you like.

See, what doubles as writing or story-telling is a matter of taking the mundane, adding two somewhat interesting people, have them do something and off you go. The guy winning the lottery has many more options in such a story.

I like options. You meet the strangest people on the way to the park.

Winning the lottery is not mundane but you still need to deal with groundhogs, who do not need the money.

Sunday, April 1, 2018

I have no idea, yet

I just finished a novel that started out as a paranormal suspense yarn and became something of a murder mystery. It's about writing what I know as opposed to what I think I know.

The main character wasn't clear to me until the second chapter and I created her out of a notion that she needed to be somewhat different. So I made her young, black and naive.

Of the three, the part that I resemble is naive, though not so much these days. In any case, it was fun taking this character through a maze of peculiar events, eclectic notions and a brutal winter in a place that probably exists in this form.

I have no idea what it will resemble when it's undergone its first back-read. I think the characters are somewhat one dimensional. The story is a bit of a stretch but -- as murder mysteries go -- it's feasible.

I am happy I did this thing and I hope I can rescue it.

The problems that remain are whether I see this story as it should be or whether I see it as I think it should be.

Writing is fun; self-criticism is less enjoyable.

I am excited about sharing it with a couple of beta readers who I trust will be harsh, kind, honest and abundantly generous with their praise of my writing skill.

One likes to hear that, doesn't one?

The main character wasn't clear to me until the second chapter and I created her out of a notion that she needed to be somewhat different. So I made her young, black and naive.

Of the three, the part that I resemble is naive, though not so much these days. In any case, it was fun taking this character through a maze of peculiar events, eclectic notions and a brutal winter in a place that probably exists in this form.

I have no idea what it will resemble when it's undergone its first back-read. I think the characters are somewhat one dimensional. The story is a bit of a stretch but -- as murder mysteries go -- it's feasible.

I am happy I did this thing and I hope I can rescue it.

The problems that remain are whether I see this story as it should be or whether I see it as I think it should be.

Writing is fun; self-criticism is less enjoyable.

I am excited about sharing it with a couple of beta readers who I trust will be harsh, kind, honest and abundantly generous with their praise of my writing skill.

One likes to hear that, doesn't one?

Tuesday, March 13, 2018

Weather as a plot device

Climate, whether it is changing too fast to suit you or is too slow showing off its really cool stuff, is an important part of a story.

The nastier the better if you want to churn up some deviant behavior. Nothing like a blizzard or flood to turn a tough time into a really bad day.

The best part of winter is that it happens partly around the Christmas holidays, which can create issues with people who are, say ... in need of government help.

"The director is out of town until the fifth of January. Is there someone else who can help you?"

"The damned dam is about to collapse and I NEED the director's permission to do ... um ... who else can help me?"

Conversely, summer heat and humidity are nice tools for driving rural stories. (Hot town, summer in the city.)

So you get that sort of option when creating dramatic tension with weather as a primary component of the yarn you want to spin.

Volcanoes, earthquakes, tidal waves are all interesting and powerful devices, but frequently they are major events that create settings. It's less likely you can write effectively about a volcano since I'd wager you have never experienced one. The last tidal wave to visit Indiana was ... yeah, you got no idea about that either, do you?

A gloomy winter helps develop characters. Unless you live in San Diego, you should be able to communicate that.

Pay some attention to the weather when starting a novel, remembering that today's blizzard is tomorrow's lost dog in the snow. Weather might not be the primary driver of the story but it adds sidebars and makes the routine somewhat unpredictable.

And the real weather you experience has affected your emotional outlook on life. Prepare to understand yourself.

The nastier the better if you want to churn up some deviant behavior. Nothing like a blizzard or flood to turn a tough time into a really bad day.

The best part of winter is that it happens partly around the Christmas holidays, which can create issues with people who are, say ... in need of government help.

"The director is out of town until the fifth of January. Is there someone else who can help you?"

"The damned dam is about to collapse and I NEED the director's permission to do ... um ... who else can help me?"

Conversely, summer heat and humidity are nice tools for driving rural stories. (Hot town, summer in the city.)

So you get that sort of option when creating dramatic tension with weather as a primary component of the yarn you want to spin.

Volcanoes, earthquakes, tidal waves are all interesting and powerful devices, but frequently they are major events that create settings. It's less likely you can write effectively about a volcano since I'd wager you have never experienced one. The last tidal wave to visit Indiana was ... yeah, you got no idea about that either, do you?

A gloomy winter helps develop characters. Unless you live in San Diego, you should be able to communicate that.

Pay some attention to the weather when starting a novel, remembering that today's blizzard is tomorrow's lost dog in the snow. Weather might not be the primary driver of the story but it adds sidebars and makes the routine somewhat unpredictable.

And the real weather you experience has affected your emotional outlook on life. Prepare to understand yourself.

Friday, March 9, 2018

Six of one ...

Lucky for me, most of what I read is bereft of cliches. I try to avoid sports reporting, political writing in conjunction with the stock market and almost anything dealing with arguments between birth control users and people who think Viagra is birth control.

That leaves me with real writing. Back in my years, I fought gamely against lazy headline writers and reporters who thought the clever turn of a phrase was unique. Borrowing from last year's issue doesn't make it anything but tedious.

In my attempts to create solid narrative, I find myself noticing what I write, wondering if the cliche (or overdone phrase) is useful or if it's a roadblock to a better verb,

I like verbs.

Naturally, a quippy turn of a phrase when least expected can create some interesting literary abrasion. It can help ease the tedium.

So long as it isn't a crutch. Depending on the cliche to tell a story suggests something is missing, that mainly being depth in the development of the character.

I think characters speak in cliches, but they're not likely advancing the story if they do much of it and it suggests strongly they aren't very interesting.

By and large, I avoid cliches like the plague.

That leaves me with real writing. Back in my years, I fought gamely against lazy headline writers and reporters who thought the clever turn of a phrase was unique. Borrowing from last year's issue doesn't make it anything but tedious.

In my attempts to create solid narrative, I find myself noticing what I write, wondering if the cliche (or overdone phrase) is useful or if it's a roadblock to a better verb,

I like verbs.

Naturally, a quippy turn of a phrase when least expected can create some interesting literary abrasion. It can help ease the tedium.

So long as it isn't a crutch. Depending on the cliche to tell a story suggests something is missing, that mainly being depth in the development of the character.

I think characters speak in cliches, but they're not likely advancing the story if they do much of it and it suggests strongly they aren't very interesting.

By and large, I avoid cliches like the plague.

Thursday, March 1, 2018

Ben Hur: more than a movie

How do you describe setting?

I think the secret lies in some of the older writing, meaning ... from the 19th century. It's important to understand that writers from the days before television or even cinema had few visual images of the worlds they described. Unless they'd been there -- and some of the more prominent writers of the day did travel a lot -- they had only other books, maps and acquaintances as reference. Diaries and journals helped. Photographs were less useful.

One can see a mountain and visualize life on it. To visualize it and describe it, two topics. The reader almost certainly had not seen this mountain. It's also important to remember that extensive travel was, depending on the area, not easily achieved by the masses.

In fact, most people of the time could scarcely afford the book, let alone the dream of experiencing what it described.

Some of that deals with verbs. They make birds fly, people sing and jump and dance. They make bears roar and trains rumble. I still don't know how many ways there are (were) to describe what people do when they are standing around, talking to each other.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.

But you are there with this paragraph.

When the dromedary lifted itself out of the last break of the wady, the traveler had passed the boundary of El Belka, the ancient Ammon. It was morning-time. Before him was the sun, half curtained in fleecy mist; before him also spread the desert; not the realm of drifting sands, which was farther on, but the region where the herbage began to dwarf; where the surface is strewn with boulders of granite, and gray and brown stones, interspersed with languishing acacias and tufts of camel-grass. The oak, bramble, and arbutus lay behind, as if they had come to a line, looked over into the well-less waste and crouched with fear.

Modern writers might describe this scene in much the same way, but the cadence of the writing will have changed. That's natural. It's what makes the craft so appealing.

Wallace was a master at painting a scene. Again, the language and cadence of the day:

At this age the apartment alluded to would be termed a saloon. It was quite spacious, floored with polished marble slabs, and lighted in the day by skylights in which colored mica served as glass. The walls were broken by Atlantes, no two of which were alike, but all supporting a cornice wrought with arabesques exceedingly intricate in form, and more elegant on account of superadditions of color -- blue, green, Tyrian purple, and gold. Around the room ran a continuous divan of Indian silks and wool of Cashmere. The furniture consisted of tables and stools of Egyptian patterns grotesquely carved.

Setting, and what makes it important. Wallace nails it here:

His shoes were brought him, and in a few minutes Ben-Hur sallied out to find the fair Egyptian. The shadow of the mountains was creeping over the Orchard of Palms in advance of night. Afar through the trees came the tinkling of sheep bells, the lowing of cattle, and the voices of the herdsmen bringing their charges home. Life at the Orchard, it should be remembered, was in all respects as pastoral as life on the scantier meadows of the desert.

If you only saw the movie, you missed the best part of this story.

I think the secret lies in some of the older writing, meaning ... from the 19th century. It's important to understand that writers from the days before television or even cinema had few visual images of the worlds they described. Unless they'd been there -- and some of the more prominent writers of the day did travel a lot -- they had only other books, maps and acquaintances as reference. Diaries and journals helped. Photographs were less useful.

One can see a mountain and visualize life on it. To visualize it and describe it, two topics. The reader almost certainly had not seen this mountain. It's also important to remember that extensive travel was, depending on the area, not easily achieved by the masses.

In fact, most people of the time could scarcely afford the book, let alone the dream of experiencing what it described.

Some of that deals with verbs. They make birds fly, people sing and jump and dance. They make bears roar and trains rumble. I still don't know how many ways there are (were) to describe what people do when they are standing around, talking to each other.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.

Still, the classics of the 19th century can give us some direction. Here is a snippet from the 1884 novel "Ben Hur, A Tale of the Christ," by Gen. Lew Wallace. The general has taken us to a land of fantasy, nothing like the landscape he knew as a child in Indiana or later, as a military man in faraway places like New or Old Mexico.But you are there with this paragraph.

When the dromedary lifted itself out of the last break of the wady, the traveler had passed the boundary of El Belka, the ancient Ammon. It was morning-time. Before him was the sun, half curtained in fleecy mist; before him also spread the desert; not the realm of drifting sands, which was farther on, but the region where the herbage began to dwarf; where the surface is strewn with boulders of granite, and gray and brown stones, interspersed with languishing acacias and tufts of camel-grass. The oak, bramble, and arbutus lay behind, as if they had come to a line, looked over into the well-less waste and crouched with fear.

Modern writers might describe this scene in much the same way, but the cadence of the writing will have changed. That's natural. It's what makes the craft so appealing.

Wallace was a master at painting a scene. Again, the language and cadence of the day:

At this age the apartment alluded to would be termed a saloon. It was quite spacious, floored with polished marble slabs, and lighted in the day by skylights in which colored mica served as glass. The walls were broken by Atlantes, no two of which were alike, but all supporting a cornice wrought with arabesques exceedingly intricate in form, and more elegant on account of superadditions of color -- blue, green, Tyrian purple, and gold. Around the room ran a continuous divan of Indian silks and wool of Cashmere. The furniture consisted of tables and stools of Egyptian patterns grotesquely carved.

Setting, and what makes it important. Wallace nails it here:

His shoes were brought him, and in a few minutes Ben-Hur sallied out to find the fair Egyptian. The shadow of the mountains was creeping over the Orchard of Palms in advance of night. Afar through the trees came the tinkling of sheep bells, the lowing of cattle, and the voices of the herdsmen bringing their charges home. Life at the Orchard, it should be remembered, was in all respects as pastoral as life on the scantier meadows of the desert.

If you only saw the movie, you missed the best part of this story.

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

Verbs that aren't

A billion years ago, a writing coach told me that if I wanted to succeed at the craft on any level, that I should avoid the following:

IS

ARE

WAS

WERE

The four weakest verbs in the English language.

The first thought was (is) that there are (is) not much way to avoid that.

Well, yes there is (was).

The trick, you see, is (was) to use verbs that sing, that drive the story. The better the verb, the better the description.

In a sense, the way to make better sentences is (was) to use verbs that do something.

There is a tree in the yard.

The tree in the yard stood like a gigantic monument to time.

It is (was) still a tree, but we have some idea of its dimensions, once we realize that the tree stands in the yard, which I suppose is (was) different from it lying on its side.

Powerful verbs help a writer because powerful verbs create a need to produce better descriptions. Verbs move our lives.

Try it sometime. Take your average sentence, even one so benign as "I am talking on the phone" and turn it into something far more dramatic.

The best authors seldom rely on is-are-was-were for description.

There are (were) times when those verbs are (were) helpful.

Try to think of something better.

IS

ARE

WAS

WERE

The four weakest verbs in the English language.

The first thought was (is) that there are (is) not much way to avoid that.

Well, yes there is (was).

The trick, you see, is (was) to use verbs that sing, that drive the story. The better the verb, the better the description.

In a sense, the way to make better sentences is (was) to use verbs that do something.

There is a tree in the yard.

The tree in the yard stood like a gigantic monument to time.

It is (was) still a tree, but we have some idea of its dimensions, once we realize that the tree stands in the yard, which I suppose is (was) different from it lying on its side.

Powerful verbs help a writer because powerful verbs create a need to produce better descriptions. Verbs move our lives.

Try it sometime. Take your average sentence, even one so benign as "I am talking on the phone" and turn it into something far more dramatic.

The best authors seldom rely on is-are-was-were for description.

There are (were) times when those verbs are (were) helpful.

Try to think of something better.

Old as dirt Part II

I have no compelling reason to include a second or even a third component to the principle that literary life lies only in the depths of our past.

A search of century-old newspapers produces all of that; modern newspapers and other publications do the same thing. The major difference is history is sealed. The present has yet to become the history, and it's far more difficult to pin down.

Let's just say: Reading about the past is as much about what did not happen as what did happen. Everyone has seen the past; almost nobody has seen the future and it's likely I don't agree with your vision of it.

That's important when considering a story written in contemporary times, one that leads inevitably to a focus on the what-ifs that manifest as the future.

The weapons of war in 1918 have been defined, and we know what impact they had. What the Pentagon is dreaming up today lives in our imagination. We simply do NOT need to re-create a light saber or focus-based ray gun for future killing. It's been done. When all else fails, produce a race of super-smart people and you can invent any damned thing you want.

The reality is machines aren't made that way. They are tools that are modified and enhanced as the result of other inventions.

New stuff is being invented every day.

Which is sort of the point of the old newspapers. They're chock-full of tidbits about flying aerocraft, machines that milk cows, medicines, sewage treatment plants, long-lasting electric light bulbs.

And ruts in the road, hogs on the train tracks, people dying of typhoid.

Simply put, we can approach any event from two directions, from now looking back and from now looking forward. It's the 'from now' part that flattens it out.

One approach isn't better than the other.

It's been said that any three people can come together over the carcass of a skunk in the middle of a county road and become the framework of a novel.

The century-old newspapers -- the better ones are the small-town weeklies -- are simply loaded with characters, stories, anecdotes and events. These stories are the front door to the future.

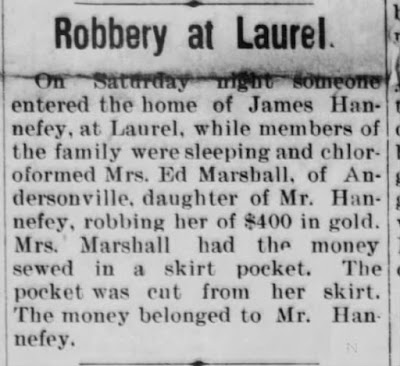

Consider the attached clip.

Chloroform? Was that a common product in 1917? Seems like an inside job if the robber knew where to look. Why would somebody have that much money sewn into a pocket. Gold? This is rural Indiana.

Sounds like a pretty damned interesting mystery novel to me. You could even turn this into a romance.

Just ordinary stuff in the average weekly newspaper.

This one from 1920:

Everything about this real event sounds and smells like "To Kill A Mockingbird." If you can't write a story about this event, the people who would be central to it and its potential outcome, take time to sniff the coffee. "Believed to be negroes ..." is focal. Looks a bit like Ernest is tryin' to pin a crime on some imaginary evil people. (Probably owed somebody money.)

In short:

Get your head out of the future and stop pretending that everything that isn't real is somehow better.

A search of century-old newspapers produces all of that; modern newspapers and other publications do the same thing. The major difference is history is sealed. The present has yet to become the history, and it's far more difficult to pin down.

Let's just say: Reading about the past is as much about what did not happen as what did happen. Everyone has seen the past; almost nobody has seen the future and it's likely I don't agree with your vision of it.

That's important when considering a story written in contemporary times, one that leads inevitably to a focus on the what-ifs that manifest as the future.

The weapons of war in 1918 have been defined, and we know what impact they had. What the Pentagon is dreaming up today lives in our imagination. We simply do NOT need to re-create a light saber or focus-based ray gun for future killing. It's been done. When all else fails, produce a race of super-smart people and you can invent any damned thing you want.

The reality is machines aren't made that way. They are tools that are modified and enhanced as the result of other inventions.

New stuff is being invented every day.

Which is sort of the point of the old newspapers. They're chock-full of tidbits about flying aerocraft, machines that milk cows, medicines, sewage treatment plants, long-lasting electric light bulbs.

And ruts in the road, hogs on the train tracks, people dying of typhoid.

Simply put, we can approach any event from two directions, from now looking back and from now looking forward. It's the 'from now' part that flattens it out.

One approach isn't better than the other.

It's been said that any three people can come together over the carcass of a skunk in the middle of a county road and become the framework of a novel.

The century-old newspapers -- the better ones are the small-town weeklies -- are simply loaded with characters, stories, anecdotes and events. These stories are the front door to the future.

Consider the attached clip.

Chloroform? Was that a common product in 1917? Seems like an inside job if the robber knew where to look. Why would somebody have that much money sewn into a pocket. Gold? This is rural Indiana.

Sounds like a pretty damned interesting mystery novel to me. You could even turn this into a romance.

Just ordinary stuff in the average weekly newspaper.

This one from 1920:

Everything about this real event sounds and smells like "To Kill A Mockingbird." If you can't write a story about this event, the people who would be central to it and its potential outcome, take time to sniff the coffee. "Believed to be negroes ..." is focal. Looks a bit like Ernest is tryin' to pin a crime on some imaginary evil people. (Probably owed somebody money.)

In short:

Get your head out of the future and stop pretending that everything that isn't real is somehow better.

Monday, February 26, 2018

Old as dirt, Part I

Part of my love of writing connects to the writer as much as the subject matter. Nothing illustrates this more than weekly newspapers from a century or more ago.

To preface, the men (and there were a few women, though usually unnamed) who published these newspapers were not journalists. They had no training in the craft. Their grammar was at times suspect and their opinions were scarcely contained on the op-ed page.

If they thought something was a big deal, it was a big deal. Where it appeared in the paper had almost nothing to do with that. That was called production. Hot metal. Galleys. Turtles. You will never experience that.

I came across a lot of fun stuff in 2015 when I did a bicentennial blog. Since then, I have found my love for old newspapers to be nothing short of zealous.

It's about the adjective.

The point of view.

The point of view.

It's about what we were told, not what we know.

It's about life.

The old newspapers from a century ago are the front door to the future. No writer of serious merit ought to overlook them. The idea well is nearly bottomless. The articles are fascinating on a lot of levels, the main one being a presumption that being odd, sick, alone, poor or awesome was just ... well, everybody's business.

To preface, the men (and there were a few women, though usually unnamed) who published these newspapers were not journalists. They had no training in the craft. Their grammar was at times suspect and their opinions were scarcely contained on the op-ed page.

If they thought something was a big deal, it was a big deal. Where it appeared in the paper had almost nothing to do with that. That was called production. Hot metal. Galleys. Turtles. You will never experience that.

I came across a lot of fun stuff in 2015 when I did a bicentennial blog. Since then, I have found my love for old newspapers to be nothing short of zealous.

It's about the adjective.

The point of view.

The point of view.It's about what we were told, not what we know.

It's about life.

The old newspapers from a century ago are the front door to the future. No writer of serious merit ought to overlook them. The idea well is nearly bottomless. The articles are fascinating on a lot of levels, the main one being a presumption that being odd, sick, alone, poor or awesome was just ... well, everybody's business.

World building Part III

The first part of any story I read that centers around world building is that the premise is predictable:

It's US against THEM, WE are the underdog and THEY are truly evil with almost unlimited resources.

All WE need to do is outrun the hare and collect the golden chalice from the grateful king at the grand ceremony. Of course, the race is fixed.

I'd be OK with that premise if I knew a real good reason why THEY are always evil and WE are always the underdog. Naturally, it's about control. It's also about human behavior, which seems contradictory in the sense that the world we're building is anything but that.

The best part of this sort of story is that we can imply that the evil ones, or THEM, are either part machine or mostly heartless and soul-barren beast. That allows US to get credit for slaying THEM for the greater good with impunity.

Hell, even on Earth, there are those who think the cockroach is God's creature. Read that sentence again, please.

Most world building comes from the Saturday morning cartoon, a genre that fully exploits our right and duty to murder anything that represents THEM, because as we know it, THEY ain't human.

And THEY want to subjugate US for reasons that just make sense.

Stop me if I ever try to write this story.

It's US against THEM, WE are the underdog and THEY are truly evil with almost unlimited resources.

All WE need to do is outrun the hare and collect the golden chalice from the grateful king at the grand ceremony. Of course, the race is fixed.

I'd be OK with that premise if I knew a real good reason why THEY are always evil and WE are always the underdog. Naturally, it's about control. It's also about human behavior, which seems contradictory in the sense that the world we're building is anything but that.

The best part of this sort of story is that we can imply that the evil ones, or THEM, are either part machine or mostly heartless and soul-barren beast. That allows US to get credit for slaying THEM for the greater good with impunity.

Hell, even on Earth, there are those who think the cockroach is God's creature. Read that sentence again, please.

Most world building comes from the Saturday morning cartoon, a genre that fully exploits our right and duty to murder anything that represents THEM, because as we know it, THEY ain't human.

And THEY want to subjugate US for reasons that just make sense.

Stop me if I ever try to write this story.

Saturday, February 24, 2018

World building -- Part II

I watched a BBC television series that explored the birth and growth of something I really hadn't considered previously:

The English language.

We know that English is a diverse and complex language, though compared to others that I don't understand, I can't say if it's THE most complex. Asian alphabets blow my mind. They look like they are a lot of work.

Aside from that, if you know your tongue, you speak it and rarely do you consider that there are three or four ways to describe a 4-legged farm animal known as a hog.

Sow, pig, swing, porker ... oink oink oink.

To the point, for writers who would build worlds with new and exciting people and places, events, tragedies, dangers, love, hate, fear ... all emotions that are based on human knowledge ... on account of, it's hard to talk to your cat about emotional issues that occur under the coffee table where Tabby hangs out.

But people on other planets don't speak like we do. How do I know this? Because people in Mexico don't speak like I do and it's a fuggavalot closer. People in Mexico don't speak like people in Spain, and neither of them speak like the native tribes, who spoke differently before Spain tried to make Mexico speak like it does.

All that has changed over the centuries. English from the 16th century is hardly discernible. It's not close to the tongue they wrote in Beowulf's time.

So if you are building a world and pretend English is just 'what it is,' you don't know your language. Even the experts ignored that.

Arthur C. Clarke, the master of science fiction, had his characters speaking a dialect and tongue that would have been much different in reality -- because some of it just would naturally have changed. It would have changed because that's what language does. There are hundreds of words in Russian now that didn't exist in the 1950s.

Writers who endeavor to do world building need to learn to write new languages -- though getting us to understand them is a craft. The novel 1984 called it Newspeak. Orwell was a genius!

And we're at that point if 'u' know what I mean. 'b4' long that will be.

Listen to the music. That will guide you. If that's not clear, listen to the people who listen to the music. If you are over 50 and you can't understand them, Orwell was probably right.

The English language.

We know that English is a diverse and complex language, though compared to others that I don't understand, I can't say if it's THE most complex. Asian alphabets blow my mind. They look like they are a lot of work.

Aside from that, if you know your tongue, you speak it and rarely do you consider that there are three or four ways to describe a 4-legged farm animal known as a hog.

Sow, pig, swing, porker ... oink oink oink.

To the point, for writers who would build worlds with new and exciting people and places, events, tragedies, dangers, love, hate, fear ... all emotions that are based on human knowledge ... on account of, it's hard to talk to your cat about emotional issues that occur under the coffee table where Tabby hangs out.

But people on other planets don't speak like we do. How do I know this? Because people in Mexico don't speak like I do and it's a fuggavalot closer. People in Mexico don't speak like people in Spain, and neither of them speak like the native tribes, who spoke differently before Spain tried to make Mexico speak like it does.

All that has changed over the centuries. English from the 16th century is hardly discernible. It's not close to the tongue they wrote in Beowulf's time.

So if you are building a world and pretend English is just 'what it is,' you don't know your language. Even the experts ignored that.

Arthur C. Clarke, the master of science fiction, had his characters speaking a dialect and tongue that would have been much different in reality -- because some of it just would naturally have changed. It would have changed because that's what language does. There are hundreds of words in Russian now that didn't exist in the 1950s.

Writers who endeavor to do world building need to learn to write new languages -- though getting us to understand them is a craft. The novel 1984 called it Newspeak. Orwell was a genius!

And we're at that point if 'u' know what I mean. 'b4' long that will be.

Listen to the music. That will guide you. If that's not clear, listen to the people who listen to the music. If you are over 50 and you can't understand them, Orwell was probably right.

World building -- Part I

Every November, I log into the NaNoWriMo convention, which is where the world's authors gather online to ask such questions as: If I have a story that happens in 1850, how many stars would be on the American flag?

Others are less amusing, more to the point of: WTF did you have in mind when you decided on the title?

The main one is the absurd notion that a high school student can freely express a unique point of view that carries over into a salable novel.

Alleging a superb level of intellect based on an eclectic and diverse life experience, most of these wannabes are driven by a story in their heads that they learned playing video games. "Wow, I could invent Zepidoptera, the stalwart defender of justice with Double-Ds, a ba-dass attitude and a generally subtle streak of generosity, sincere love and affection for her true ..." ........... stop me here before I have to get a plastic bag.

World building, to a fan of cartoon fiction, is quite simple.

There are various parts to this, the chief one being ... where exactly is this world you just built? Well, in some other "galaxy," is the standard answer -- as if the one they're in isn't big enough.

But the main parts of this relate to how one gets there, why they chose to go there, or how we knew they were there if they were already there.

More subtle components all mesh what the potential writer knows, and how to modify it.

We need a whole lot less of this "literature" and a whole lot less promoting of it as a form of writing.

NaNoWriMo is an interesting place to visit when going off-world. Almost nobody who participates has any concept of how to write a novel and they aren't getting much in the way of help. Rooting somebody on is fairly free, hardly of any value.

I have no idea what percentage of Wrimos get a real book written. I suspect less than a percent or two. Most of them have no idea how to research and fewer have actually read very much. When you're 17, you aren't ready to write a novel.

No matter which world you inhabit.

Others are less amusing, more to the point of: WTF did you have in mind when you decided on the title?

The main one is the absurd notion that a high school student can freely express a unique point of view that carries over into a salable novel.

Alleging a superb level of intellect based on an eclectic and diverse life experience, most of these wannabes are driven by a story in their heads that they learned playing video games. "Wow, I could invent Zepidoptera, the stalwart defender of justice with Double-Ds, a ba-dass attitude and a generally subtle streak of generosity, sincere love and affection for her true ..." ........... stop me here before I have to get a plastic bag.

World building, to a fan of cartoon fiction, is quite simple.

There are various parts to this, the chief one being ... where exactly is this world you just built? Well, in some other "galaxy," is the standard answer -- as if the one they're in isn't big enough.

But the main parts of this relate to how one gets there, why they chose to go there, or how we knew they were there if they were already there.

More subtle components all mesh what the potential writer knows, and how to modify it.

We need a whole lot less of this "literature" and a whole lot less promoting of it as a form of writing.

NaNoWriMo is an interesting place to visit when going off-world. Almost nobody who participates has any concept of how to write a novel and they aren't getting much in the way of help. Rooting somebody on is fairly free, hardly of any value.

I have no idea what percentage of Wrimos get a real book written. I suspect less than a percent or two. Most of them have no idea how to research and fewer have actually read very much. When you're 17, you aren't ready to write a novel.

No matter which world you inhabit.

Friday, February 23, 2018

Histronomical fiction, fun without the laughs

I'm getting a kick out of my search for an agent or publisher, mainly because I'd originally intended Hannah's Valley to be what is loosely called historical fiction.

The second part is true. It's a fiction.

How historical is it?

Well, it's in the past and could have happened.

So that's pretty much the genre, defined.

Most agents who allude to wanting historical fiction have been so far pretty vague about what that includes. Naturally, we want to know: How old does it have to be before it's historical? The standard notion is that it somehow needs to be no newer than the 19th century. That's important because of the morals, the dress code and of course, the regal settings. So 'historical' is an excuse to embellish location, location, location. If it ain't in the palace, it's not very interesting.

So if you wrote about a Navy ship off the coast of Honduras from 2001, would that be historical?

A yarn about the days just after 9/11 would scarcely be historical to me since it's generally available by clicking a Google search.

Hell, almost everything is generally available that way.

Still, are we talking ... oh, the time of Jesus or the time of Jimmy?

Does historical fiction, as presented in novel form, just look like something you scraped up by doing a few Wikipedia searches?

Hannah's Valley is as accurate historically as I want it to be. There are no motorboats in the river because it's 1866. They didn't even have AA batteries for their flashlights.

But the question about whether a woman wore a bonnet or a floppy hat would depend on one's interpretation of the fashion of the day. How they talked is kind of important, and their education level was as we might expect it to be.

But it's not historical. It's just set in another time. It's a novel, and it's a story about people. Nobody got gunned down. Well, sorry ... yes, one guy did get gunned down. But he was an asshole.

I can't prove Hannah's Valley didn't happen, but neither can you.

The second part is true. It's a fiction.

How historical is it?

Well, it's in the past and could have happened.

So that's pretty much the genre, defined.

Most agents who allude to wanting historical fiction have been so far pretty vague about what that includes. Naturally, we want to know: How old does it have to be before it's historical? The standard notion is that it somehow needs to be no newer than the 19th century. That's important because of the morals, the dress code and of course, the regal settings. So 'historical' is an excuse to embellish location, location, location. If it ain't in the palace, it's not very interesting.

So if you wrote about a Navy ship off the coast of Honduras from 2001, would that be historical?

A yarn about the days just after 9/11 would scarcely be historical to me since it's generally available by clicking a Google search.

Hell, almost everything is generally available that way.

Still, are we talking ... oh, the time of Jesus or the time of Jimmy?

Does historical fiction, as presented in novel form, just look like something you scraped up by doing a few Wikipedia searches?

Hannah's Valley is as accurate historically as I want it to be. There are no motorboats in the river because it's 1866. They didn't even have AA batteries for their flashlights.

But the question about whether a woman wore a bonnet or a floppy hat would depend on one's interpretation of the fashion of the day. How they talked is kind of important, and their education level was as we might expect it to be.

But it's not historical. It's just set in another time. It's a novel, and it's a story about people. Nobody got gunned down. Well, sorry ... yes, one guy did get gunned down. But he was an asshole.

I can't prove Hannah's Valley didn't happen, but neither can you.

Thursday, February 22, 2018

When werewolves won't leave you alone

A trillion light years ago, back when the two-lane highway was a super slab if it didn't have 90-degree turns in it, I was leaving work.

A trillion light years ago, back when the two-lane highway was a super slab if it didn't have 90-degree turns in it, I was leaving work.It was around 1 a.m., give or take an hour.

Midnight seems too obvious for this story.

The focking fug was so thick -- how thick WAS it -- that I could barely see the road. I could tell I was on the road because, well the screaming in agony of the earthworms would have been abundant evidence.

In the distance, a couple of little yellow lights approached me.

Or was it?

The lights never got bigger, or brighter ... as one would expect from an oncoming car on a foggy night in rural Indiana. You just would expect that to happen.

Then a whisk of black went whishing by, as whishing things are wont do do.

I knew in an instant what I'd seen.

A wucking fearwolf.

I had nearly hit those yellow eyes in the focking fug, and I was grateful that I had not contributed to the runaway carnage that happens on such nights in rural Indiana. To be sure, I'd already saved countless earthworms from certain doom.

The werewolf followed my car, evidently angry that I'd interrupted its sojourn across U.S. 27 three miles south of Richmond, or a mile west of Boston, a mile east of Abington. Not far from the state TB hospital.

Right in there somewhere.

The creature followed me home and the next day, I saw scratch marks on the hood of my car, marks that were not of this world.

Many years later, to shorten this story, I wrote a novel about that night, mixing in some truth with a tad of embellishment. The real facts are way too frightening to share.

I'd like somebody to buy that book.

It's about Opakwa.

It's a story not for the faint of heart.

Tuesday, February 20, 2018

Up on dry land

Usually, a blog headline has something to do with the body of the whole thing. We learned that back in J-school.

Such as: F**k you!

Now that I have your attention, please read the rest of this.

Which has nothing to do with anything, so I will alert you in advance, this blog item is about dangling modifiers.

Nasty stuff, that.

I have a couple of buds who don't write but are amazed that I do, or can. I actually realized long ago that "you" has three letters in it, and was thus rewarded with a cum laudical degree from the university.

State University.

It came around that somebody asked me how I decided what my story would be about and I said, it's about the absurdity of life. Everything is a joke if it doesn't ruin your carpet or bankrupt you.

Optionally, graveyards are either fun for frolics or something else.

I wrote a story that has been alternately titled Gone With the Wind, Grapes of Wrath or just ... Fairfield. I will come up with something better eventually. I don't want to share much about it but it's a zombie thriller with real live dead zombies that came back to life because they wanted to have fun again.

But it is about graveyards and the peculiar events that can happen in a paranormal story that make the whole process of crossing over a quite human event. That is because it was written by a human.

People are what make stories. It's what they are about and it's who they are intended to reach.

We live in a world now that is lubricated by ridiculous headlines.

Start from the back and work forward. The headline should make sense at that point.

Such as: F**k you!

Now that I have your attention, please read the rest of this.

Which has nothing to do with anything, so I will alert you in advance, this blog item is about dangling modifiers.

Nasty stuff, that.

I have a couple of buds who don't write but are amazed that I do, or can. I actually realized long ago that "you" has three letters in it, and was thus rewarded with a cum laudical degree from the university.

State University.

It came around that somebody asked me how I decided what my story would be about and I said, it's about the absurdity of life. Everything is a joke if it doesn't ruin your carpet or bankrupt you.

Optionally, graveyards are either fun for frolics or something else.

I wrote a story that has been alternately titled Gone With the Wind, Grapes of Wrath or just ... Fairfield. I will come up with something better eventually. I don't want to share much about it but it's a zombie thriller with real live dead zombies that came back to life because they wanted to have fun again.

But it is about graveyards and the peculiar events that can happen in a paranormal story that make the whole process of crossing over a quite human event. That is because it was written by a human.

People are what make stories. It's what they are about and it's who they are intended to reach.

We live in a world now that is lubricated by ridiculous headlines.

Start from the back and work forward. The headline should make sense at that point.

Taking ourselves seriously is probably a mistake

I snipped this list from Authorlink.com that is pretty succinct in what their stable of insiders think of the rest of us:

Traditional publishing may be for you if:

- You have had your book professionally edited

- You have taken the time to search for and land a literary agent who can represent your book to the traditional houses.

- Are willing to take editors’ suggestions for revisions

- Have realistic expectations about how much money you will make

- Have a solid promotional platform, such as a large website, speaking schedule, existing record of book sales or are a known celebrity.

- Are willing to wait for one to two years to see the book in print.

- Are willing to self-promote like crazy, even though a traditional publisher should be doing the job.

- Don’t mind turning over the rights to your book.

Essentially, the website that dedicates itself to writers, agents, publishers and readers has made it clear that we should probably not bother because (No. 5) we just aren't successful enough.

Dunno, but this sort of advice is the reason people publish their own books, which Authorlink is proud to advise us about as well. It's just not as interesting.

Monday, February 19, 2018

Write what you think you know

The adage about writing what we know is always a policy that makes sense. I really don't know much about hiking in the Sahara, but I can say that I'd be accurate in describing it as hot and dry without much chance of getting a ride to the nearest gas station.

Don't run out of gas. I actually did that once, so I can safely write about it with some degree of enthusiasm.

I recall getting my first PC about 20 years ago and snooping around for various websites that discussed writing. Never did I have any illusions about the craft. Writing what one knows is hardly enough if one has no idea how to structure a piece of prose that's more than five or six pages long.

So I wrote a couple of crappy novels, and I pawned them off on an e-book operation that promised me millions in royalty. Clueless, we all were. The E-book industry looked like a comer at the time. I think it missed its window and suffered broken fingers, I think I sold 3 novels.

Anyway, I still have the manuscripts for those classics and don't intend to even read them again. Well, someday ....

The funny part was, I also tripped over a few other things. Then one day, I decided to write a porn novel. No agenda, no plan, no plot ... just included as much profanity, sex and combinations thereof. I just wanted to see if I could write one. I think it took me a week. I offered it to this woman who had an "erotica" website and she took it. I made a couple of hundred dollars off the thing over a dozen years.

I sold a couple of others to a different outfit. The stuff wasn't so much porn as it was just fun stories with people doing sexual things. I called it blue-collar romance, or love stories about people who were considering being in love.

I still have that stuff around here too and have considered recasting it with a little less gravy and a few more potatoes.

But what I learned along the way is that you don't always have to write what you know. What you first need to do is learn how to write. Novels are hard work. The reward is awesome.

It's almost better than getting laid.

Don't run out of gas. I actually did that once, so I can safely write about it with some degree of enthusiasm.

I recall getting my first PC about 20 years ago and snooping around for various websites that discussed writing. Never did I have any illusions about the craft. Writing what one knows is hardly enough if one has no idea how to structure a piece of prose that's more than five or six pages long.

So I wrote a couple of crappy novels, and I pawned them off on an e-book operation that promised me millions in royalty. Clueless, we all were. The E-book industry looked like a comer at the time. I think it missed its window and suffered broken fingers, I think I sold 3 novels.

Anyway, I still have the manuscripts for those classics and don't intend to even read them again. Well, someday ....

The funny part was, I also tripped over a few other things. Then one day, I decided to write a porn novel. No agenda, no plan, no plot ... just included as much profanity, sex and combinations thereof. I just wanted to see if I could write one. I think it took me a week. I offered it to this woman who had an "erotica" website and she took it. I made a couple of hundred dollars off the thing over a dozen years.

I sold a couple of others to a different outfit. The stuff wasn't so much porn as it was just fun stories with people doing sexual things. I called it blue-collar romance, or love stories about people who were considering being in love.

I still have that stuff around here too and have considered recasting it with a little less gravy and a few more potatoes.

But what I learned along the way is that you don't always have to write what you know. What you first need to do is learn how to write. Novels are hard work. The reward is awesome.

It's almost better than getting laid.

How does one write?

Skip over the obvious. We don't have to discuss the barnyard cluck to know how to cook an omelette.

In reconstructing this blog after a long period of dormancy that connected to my former work, which I obviously no longer do, I have tried to remember the reasons one actually DOES a blog. Nobody really ever reads it. Some of my best writing on the Fairfield 200 blog has been noticed by fewer than a dozen people -- and some them ought to actually care what has been written there.

Alas not my problem.

So how does one write?

According to people who try to sell us on the notion that anybody can publish a novel, it's essentially the principle of the primate being given a ream of paper and an IBM Selectric. The Selectric was one ba-dass typewriter, so a chimp would probably adapt fairly well.

I was driving home from work one night in a fog, literally, and was enveloped by the real fear that a werewolf might jump out onto the road. I'd hit the damned thing, just wound it ... and it would come scratching at my door with an agenda. We didn't have a lot of werewolves around town in those days, but some.

Forty years later, I wrote Opakwa.

Nobody has bought that book yet, which is a damned shame.

The fog I experienced the other day was not dissimilar, but the werewolf is in another county now.

I think.

That doesn't say very much about the question: How does one write?

Dunno ... ask the monkey. He probably has an agent.

In reconstructing this blog after a long period of dormancy that connected to my former work, which I obviously no longer do, I have tried to remember the reasons one actually DOES a blog. Nobody really ever reads it. Some of my best writing on the Fairfield 200 blog has been noticed by fewer than a dozen people -- and some them ought to actually care what has been written there.

Alas not my problem.

So how does one write?

According to people who try to sell us on the notion that anybody can publish a novel, it's essentially the principle of the primate being given a ream of paper and an IBM Selectric. The Selectric was one ba-dass typewriter, so a chimp would probably adapt fairly well.

I was driving home from work one night in a fog, literally, and was enveloped by the real fear that a werewolf might jump out onto the road. I'd hit the damned thing, just wound it ... and it would come scratching at my door with an agenda. We didn't have a lot of werewolves around town in those days, but some.

Forty years later, I wrote Opakwa.

Nobody has bought that book yet, which is a damned shame.

The fog I experienced the other day was not dissimilar, but the werewolf is in another county now.

I think.

That doesn't say very much about the question: How does one write?

Dunno ... ask the monkey. He probably has an agent.

The art of being published

It's been said that we are divided into two groups:

Those who divide people into two groups, and those who do not.

At first glance, this requires more thought.

It's deeper than it appears.

There are those of us who are published authors and there are those of us who are encouraged to be so.

The problem is, the traditional process has been scripted for us.

We can't get there from here.

Well, one sort of 'can' get there, but it's like being asked to walk the entire distance while the really great ones among us get to take the airplane.

This includes agents, I reckon.

I recently joined up with Authorlink.com, which is a go-to operation for people looking for agents, publishers, writing tips, advice, and offering a place to strut your stuff.

Basically, the information for people who would rather take the plane than walk was: Forget it, you'll not get a ticket.

I'm not quite that calloused yet. I wrote some stuff and it's good. I won't walk or take the plane but I will be damned if I give it away.

It's sort of a shame that the people who root us on and are in a position to help us succeed are so disinclined to actually follow up on that.

In that respect, I divide people into two groups.

Those who divide people into two groups, and those who do not.

At first glance, this requires more thought.

It's deeper than it appears.

There are those of us who are published authors and there are those of us who are encouraged to be so.

The problem is, the traditional process has been scripted for us.

We can't get there from here.

Well, one sort of 'can' get there, but it's like being asked to walk the entire distance while the really great ones among us get to take the airplane.

This includes agents, I reckon.

I recently joined up with Authorlink.com, which is a go-to operation for people looking for agents, publishers, writing tips, advice, and offering a place to strut your stuff.

Basically, the information for people who would rather take the plane than walk was: Forget it, you'll not get a ticket.

I'm not quite that calloused yet. I wrote some stuff and it's good. I won't walk or take the plane but I will be damned if I give it away.

It's sort of a shame that the people who root us on and are in a position to help us succeed are so disinclined to actually follow up on that.

In that respect, I divide people into two groups.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)