A billion years ago, a writing coach told me that if I wanted to succeed at the craft on any level, that I should avoid the following:

IS

ARE

WAS

WERE

The four weakest verbs in the English language.

The first thought was (is) that there are (is) not much way to avoid that.

Well, yes there is (was).

The trick, you see, is (was) to use verbs that sing, that drive the story. The better the verb, the better the description. In a sense, the way to make better sentences is (was) to use verbs that do something.

There is a tree in the yard.

The tree in the yard stood like a gigantic monument to time.

It is (was) still a tree, but we have some idea of its dimensions, once we realize that the tree stands in the yard, which I suppose is (was) different from it lying on its side.

Powerful verbs help a writer because powerful verbs create a need to produce better descriptions. Verbs move our lives.

Try it sometime. Take your average sentence, even one so benign as "I am talking on the phone" and turn it into something far more dramatic.

The best authors seldom rely on is-are-was-were for description.

There are (were) times when those verbs are (were) helpful.

Try to think of something better.

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

Old as dirt Part II

I have no compelling reason to include a second or even a third component to the principle that literary life lies only in the depths of our past.

A search of century-old newspapers produces all of that; modern newspapers and other publications do the same thing. The major difference is history is sealed. The present has yet to become the history, and it's far more difficult to pin down.

Let's just say: Reading about the past is as much about what did not happen as what did happen. Everyone has seen the past; almost nobody has seen the future and it's likely I don't agree with your vision of it.

That's important when considering a story written in contemporary times, one that leads inevitably to a focus on the what-ifs that manifest as the future.

The weapons of war in 1918 have been defined, and we know what impact they had. What the Pentagon is dreaming up today lives in our imagination. We simply do NOT need to re-create a light saber or focus-based ray gun for future killing. It's been done. When all else fails, produce a race of super-smart people and you can invent any damned thing you want.

The reality is machines aren't made that way. They are tools that are modified and enhanced as the result of other inventions.

New stuff is being invented every day.

Which is sort of the point of the old newspapers. They're chock-full of tidbits about flying aerocraft, machines that milk cows, medicines, sewage treatment plants, long-lasting electric light bulbs.

And ruts in the road, hogs on the train tracks, people dying of typhoid.

Simply put, we can approach any event from two directions, from now looking back and from now looking forward. It's the 'from now' part that flattens it out.

One approach isn't better than the other.

It's been said that any three people can come together over the carcass of a skunk in the middle of a county road and become the framework of a novel.

The century-old newspapers -- the better ones are the small-town weeklies -- are simply loaded with characters, stories, anecdotes and events. These stories are the front door to the future.

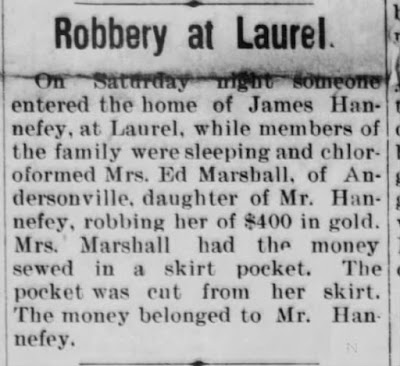

Consider the attached clip.

Chloroform? Was that a common product in 1917? Seems like an inside job if the robber knew where to look. Why would somebody have that much money sewn into a pocket. Gold? This is rural Indiana.

Sounds like a pretty damned interesting mystery novel to me. You could even turn this into a romance.

Just ordinary stuff in the average weekly newspaper.

This one from 1920:

Everything about this real event sounds and smells like "To Kill A Mockingbird." If you can't write a story about this event, the people who would be central to it and its potential outcome, take time to sniff the coffee. "Believed to be negroes ..." is focal. Looks a bit like Ernest is tryin' to pin a crime on some imaginary evil people. (Probably owed somebody money.)

In short:

Get your head out of the future and stop pretending that everything that isn't real is somehow better.

A search of century-old newspapers produces all of that; modern newspapers and other publications do the same thing. The major difference is history is sealed. The present has yet to become the history, and it's far more difficult to pin down.

Let's just say: Reading about the past is as much about what did not happen as what did happen. Everyone has seen the past; almost nobody has seen the future and it's likely I don't agree with your vision of it.

That's important when considering a story written in contemporary times, one that leads inevitably to a focus on the what-ifs that manifest as the future.

The weapons of war in 1918 have been defined, and we know what impact they had. What the Pentagon is dreaming up today lives in our imagination. We simply do NOT need to re-create a light saber or focus-based ray gun for future killing. It's been done. When all else fails, produce a race of super-smart people and you can invent any damned thing you want.

The reality is machines aren't made that way. They are tools that are modified and enhanced as the result of other inventions.

New stuff is being invented every day.

Which is sort of the point of the old newspapers. They're chock-full of tidbits about flying aerocraft, machines that milk cows, medicines, sewage treatment plants, long-lasting electric light bulbs.

And ruts in the road, hogs on the train tracks, people dying of typhoid.

Simply put, we can approach any event from two directions, from now looking back and from now looking forward. It's the 'from now' part that flattens it out.

One approach isn't better than the other.

It's been said that any three people can come together over the carcass of a skunk in the middle of a county road and become the framework of a novel.

The century-old newspapers -- the better ones are the small-town weeklies -- are simply loaded with characters, stories, anecdotes and events. These stories are the front door to the future.

Consider the attached clip.

Chloroform? Was that a common product in 1917? Seems like an inside job if the robber knew where to look. Why would somebody have that much money sewn into a pocket. Gold? This is rural Indiana.

Sounds like a pretty damned interesting mystery novel to me. You could even turn this into a romance.

Just ordinary stuff in the average weekly newspaper.

This one from 1920:

Everything about this real event sounds and smells like "To Kill A Mockingbird." If you can't write a story about this event, the people who would be central to it and its potential outcome, take time to sniff the coffee. "Believed to be negroes ..." is focal. Looks a bit like Ernest is tryin' to pin a crime on some imaginary evil people. (Probably owed somebody money.)

In short:

Get your head out of the future and stop pretending that everything that isn't real is somehow better.

Monday, February 26, 2018

Old as dirt, Part I

Part of my love of writing connects to the writer as much as the subject matter. Nothing illustrates this more than weekly newspapers from a century or more ago.

To preface, the men (and there were a few women, though usually unnamed) who published these newspapers were not journalists. They had no training in the craft. Their grammar was at times suspect and their opinions were scarcely contained on the op-ed page.

If they thought something was a big deal, it was a big deal. Where it appeared in the paper had almost nothing to do with that. That was called production. Hot metal. Galleys. Turtles. You will never experience that.

I came across a lot of fun stuff in 2015 when I did a bicentennial blog. Since then, I have found my love for old newspapers to be nothing short of zealous.

It's about the adjective.

The point of view.

The point of view.

It's about what we were told, not what we know.

It's about life.

The old newspapers from a century ago are the front door to the future. No writer of serious merit ought to overlook them. The idea well is nearly bottomless. The articles are fascinating on a lot of levels, the main one being a presumption that being odd, sick, alone, poor or awesome was just ... well, everybody's business.

To preface, the men (and there were a few women, though usually unnamed) who published these newspapers were not journalists. They had no training in the craft. Their grammar was at times suspect and their opinions were scarcely contained on the op-ed page.

If they thought something was a big deal, it was a big deal. Where it appeared in the paper had almost nothing to do with that. That was called production. Hot metal. Galleys. Turtles. You will never experience that.

I came across a lot of fun stuff in 2015 when I did a bicentennial blog. Since then, I have found my love for old newspapers to be nothing short of zealous.

It's about the adjective.

The point of view.

The point of view.It's about what we were told, not what we know.

It's about life.

The old newspapers from a century ago are the front door to the future. No writer of serious merit ought to overlook them. The idea well is nearly bottomless. The articles are fascinating on a lot of levels, the main one being a presumption that being odd, sick, alone, poor or awesome was just ... well, everybody's business.

World building Part III

The first part of any story I read that centers around world building is that the premise is predictable:

It's US against THEM, WE are the underdog and THEY are truly evil with almost unlimited resources.

All WE need to do is outrun the hare and collect the golden chalice from the grateful king at the grand ceremony. Of course, the race is fixed.

I'd be OK with that premise if I knew a real good reason why THEY are always evil and WE are always the underdog. Naturally, it's about control. It's also about human behavior, which seems contradictory in the sense that the world we're building is anything but that.

The best part of this sort of story is that we can imply that the evil ones, or THEM, are either part machine or mostly heartless and soul-barren beast. That allows US to get credit for slaying THEM for the greater good with impunity.

Hell, even on Earth, there are those who think the cockroach is God's creature. Read that sentence again, please.

Most world building comes from the Saturday morning cartoon, a genre that fully exploits our right and duty to murder anything that represents THEM, because as we know it, THEY ain't human.

And THEY want to subjugate US for reasons that just make sense.

Stop me if I ever try to write this story.

It's US against THEM, WE are the underdog and THEY are truly evil with almost unlimited resources.

All WE need to do is outrun the hare and collect the golden chalice from the grateful king at the grand ceremony. Of course, the race is fixed.

I'd be OK with that premise if I knew a real good reason why THEY are always evil and WE are always the underdog. Naturally, it's about control. It's also about human behavior, which seems contradictory in the sense that the world we're building is anything but that.

The best part of this sort of story is that we can imply that the evil ones, or THEM, are either part machine or mostly heartless and soul-barren beast. That allows US to get credit for slaying THEM for the greater good with impunity.

Hell, even on Earth, there are those who think the cockroach is God's creature. Read that sentence again, please.

Most world building comes from the Saturday morning cartoon, a genre that fully exploits our right and duty to murder anything that represents THEM, because as we know it, THEY ain't human.

And THEY want to subjugate US for reasons that just make sense.

Stop me if I ever try to write this story.

Saturday, February 24, 2018

World building -- Part II

I watched a BBC television series that explored the birth and growth of something I really hadn't considered previously:

The English language.

We know that English is a diverse and complex language, though compared to others that I don't understand, I can't say if it's THE most complex. Asian alphabets blow my mind. They look like they are a lot of work.

Aside from that, if you know your tongue, you speak it and rarely do you consider that there are three or four ways to describe a 4-legged farm animal known as a hog.

Sow, pig, swing, porker ... oink oink oink.

To the point, for writers who would build worlds with new and exciting people and places, events, tragedies, dangers, love, hate, fear ... all emotions that are based on human knowledge ... on account of, it's hard to talk to your cat about emotional issues that occur under the coffee table where Tabby hangs out.

But people on other planets don't speak like we do. How do I know this? Because people in Mexico don't speak like I do and it's a fuggavalot closer. People in Mexico don't speak like people in Spain, and neither of them speak like the native tribes, who spoke differently before Spain tried to make Mexico speak like it does.

All that has changed over the centuries. English from the 16th century is hardly discernible. It's not close to the tongue they wrote in Beowulf's time.

So if you are building a world and pretend English is just 'what it is,' you don't know your language. Even the experts ignored that.

Arthur C. Clarke, the master of science fiction, had his characters speaking a dialect and tongue that would have been much different in reality -- because some of it just would naturally have changed. It would have changed because that's what language does. There are hundreds of words in Russian now that didn't exist in the 1950s.

Writers who endeavor to do world building need to learn to write new languages -- though getting us to understand them is a craft. The novel 1984 called it Newspeak. Orwell was a genius!

And we're at that point if 'u' know what I mean. 'b4' long that will be.

Listen to the music. That will guide you. If that's not clear, listen to the people who listen to the music. If you are over 50 and you can't understand them, Orwell was probably right.

The English language.

We know that English is a diverse and complex language, though compared to others that I don't understand, I can't say if it's THE most complex. Asian alphabets blow my mind. They look like they are a lot of work.

Aside from that, if you know your tongue, you speak it and rarely do you consider that there are three or four ways to describe a 4-legged farm animal known as a hog.

Sow, pig, swing, porker ... oink oink oink.

To the point, for writers who would build worlds with new and exciting people and places, events, tragedies, dangers, love, hate, fear ... all emotions that are based on human knowledge ... on account of, it's hard to talk to your cat about emotional issues that occur under the coffee table where Tabby hangs out.

But people on other planets don't speak like we do. How do I know this? Because people in Mexico don't speak like I do and it's a fuggavalot closer. People in Mexico don't speak like people in Spain, and neither of them speak like the native tribes, who spoke differently before Spain tried to make Mexico speak like it does.

All that has changed over the centuries. English from the 16th century is hardly discernible. It's not close to the tongue they wrote in Beowulf's time.

So if you are building a world and pretend English is just 'what it is,' you don't know your language. Even the experts ignored that.

Arthur C. Clarke, the master of science fiction, had his characters speaking a dialect and tongue that would have been much different in reality -- because some of it just would naturally have changed. It would have changed because that's what language does. There are hundreds of words in Russian now that didn't exist in the 1950s.

Writers who endeavor to do world building need to learn to write new languages -- though getting us to understand them is a craft. The novel 1984 called it Newspeak. Orwell was a genius!

And we're at that point if 'u' know what I mean. 'b4' long that will be.

Listen to the music. That will guide you. If that's not clear, listen to the people who listen to the music. If you are over 50 and you can't understand them, Orwell was probably right.

World building -- Part I

Every November, I log into the NaNoWriMo convention, which is where the world's authors gather online to ask such questions as: If I have a story that happens in 1850, how many stars would be on the American flag?

Others are less amusing, more to the point of: WTF did you have in mind when you decided on the title?

The main one is the absurd notion that a high school student can freely express a unique point of view that carries over into a salable novel.

Alleging a superb level of intellect based on an eclectic and diverse life experience, most of these wannabes are driven by a story in their heads that they learned playing video games. "Wow, I could invent Zepidoptera, the stalwart defender of justice with Double-Ds, a ba-dass attitude and a generally subtle streak of generosity, sincere love and affection for her true ..." ........... stop me here before I have to get a plastic bag.

World building, to a fan of cartoon fiction, is quite simple.

There are various parts to this, the chief one being ... where exactly is this world you just built? Well, in some other "galaxy," is the standard answer -- as if the one they're in isn't big enough.

But the main parts of this relate to how one gets there, why they chose to go there, or how we knew they were there if they were already there.

More subtle components all mesh what the potential writer knows, and how to modify it.

We need a whole lot less of this "literature" and a whole lot less promoting of it as a form of writing.

NaNoWriMo is an interesting place to visit when going off-world. Almost nobody who participates has any concept of how to write a novel and they aren't getting much in the way of help. Rooting somebody on is fairly free, hardly of any value.

I have no idea what percentage of Wrimos get a real book written. I suspect less than a percent or two. Most of them have no idea how to research and fewer have actually read very much. When you're 17, you aren't ready to write a novel.

No matter which world you inhabit.

Others are less amusing, more to the point of: WTF did you have in mind when you decided on the title?

The main one is the absurd notion that a high school student can freely express a unique point of view that carries over into a salable novel.

Alleging a superb level of intellect based on an eclectic and diverse life experience, most of these wannabes are driven by a story in their heads that they learned playing video games. "Wow, I could invent Zepidoptera, the stalwart defender of justice with Double-Ds, a ba-dass attitude and a generally subtle streak of generosity, sincere love and affection for her true ..." ........... stop me here before I have to get a plastic bag.

World building, to a fan of cartoon fiction, is quite simple.

There are various parts to this, the chief one being ... where exactly is this world you just built? Well, in some other "galaxy," is the standard answer -- as if the one they're in isn't big enough.

But the main parts of this relate to how one gets there, why they chose to go there, or how we knew they were there if they were already there.

More subtle components all mesh what the potential writer knows, and how to modify it.

We need a whole lot less of this "literature" and a whole lot less promoting of it as a form of writing.

NaNoWriMo is an interesting place to visit when going off-world. Almost nobody who participates has any concept of how to write a novel and they aren't getting much in the way of help. Rooting somebody on is fairly free, hardly of any value.

I have no idea what percentage of Wrimos get a real book written. I suspect less than a percent or two. Most of them have no idea how to research and fewer have actually read very much. When you're 17, you aren't ready to write a novel.

No matter which world you inhabit.

Friday, February 23, 2018

Histronomical fiction, fun without the laughs

I'm getting a kick out of my search for an agent or publisher, mainly because I'd originally intended Hannah's Valley to be what is loosely called historical fiction.

The second part is true. It's a fiction.

How historical is it?

Well, it's in the past and could have happened.

So that's pretty much the genre, defined.

Most agents who allude to wanting historical fiction have been so far pretty vague about what that includes. Naturally, we want to know: How old does it have to be before it's historical? The standard notion is that it somehow needs to be no newer than the 19th century. That's important because of the morals, the dress code and of course, the regal settings. So 'historical' is an excuse to embellish location, location, location. If it ain't in the palace, it's not very interesting.

So if you wrote about a Navy ship off the coast of Honduras from 2001, would that be historical?

A yarn about the days just after 9/11 would scarcely be historical to me since it's generally available by clicking a Google search.

Hell, almost everything is generally available that way.

Still, are we talking ... oh, the time of Jesus or the time of Jimmy?

Does historical fiction, as presented in novel form, just look like something you scraped up by doing a few Wikipedia searches?

Hannah's Valley is as accurate historically as I want it to be. There are no motorboats in the river because it's 1866. They didn't even have AA batteries for their flashlights.

But the question about whether a woman wore a bonnet or a floppy hat would depend on one's interpretation of the fashion of the day. How they talked is kind of important, and their education level was as we might expect it to be.

But it's not historical. It's just set in another time. It's a novel, and it's a story about people. Nobody got gunned down. Well, sorry ... yes, one guy did get gunned down. But he was an asshole.

I can't prove Hannah's Valley didn't happen, but neither can you.

The second part is true. It's a fiction.

How historical is it?

Well, it's in the past and could have happened.

So that's pretty much the genre, defined.

Most agents who allude to wanting historical fiction have been so far pretty vague about what that includes. Naturally, we want to know: How old does it have to be before it's historical? The standard notion is that it somehow needs to be no newer than the 19th century. That's important because of the morals, the dress code and of course, the regal settings. So 'historical' is an excuse to embellish location, location, location. If it ain't in the palace, it's not very interesting.

So if you wrote about a Navy ship off the coast of Honduras from 2001, would that be historical?

A yarn about the days just after 9/11 would scarcely be historical to me since it's generally available by clicking a Google search.

Hell, almost everything is generally available that way.

Still, are we talking ... oh, the time of Jesus or the time of Jimmy?

Does historical fiction, as presented in novel form, just look like something you scraped up by doing a few Wikipedia searches?

Hannah's Valley is as accurate historically as I want it to be. There are no motorboats in the river because it's 1866. They didn't even have AA batteries for their flashlights.

But the question about whether a woman wore a bonnet or a floppy hat would depend on one's interpretation of the fashion of the day. How they talked is kind of important, and their education level was as we might expect it to be.

But it's not historical. It's just set in another time. It's a novel, and it's a story about people. Nobody got gunned down. Well, sorry ... yes, one guy did get gunned down. But he was an asshole.

I can't prove Hannah's Valley didn't happen, but neither can you.

Thursday, February 22, 2018

When werewolves won't leave you alone

A trillion light years ago, back when the two-lane highway was a super slab if it didn't have 90-degree turns in it, I was leaving work.

A trillion light years ago, back when the two-lane highway was a super slab if it didn't have 90-degree turns in it, I was leaving work.It was around 1 a.m., give or take an hour.

Midnight seems too obvious for this story.

The focking fug was so thick -- how thick WAS it -- that I could barely see the road. I could tell I was on the road because, well the screaming in agony of the earthworms would have been abundant evidence.

In the distance, a couple of little yellow lights approached me.

Or was it?

The lights never got bigger, or brighter ... as one would expect from an oncoming car on a foggy night in rural Indiana. You just would expect that to happen.

Then a whisk of black went whishing by, as whishing things are wont do do.

I knew in an instant what I'd seen.

A wucking fearwolf.

I had nearly hit those yellow eyes in the focking fug, and I was grateful that I had not contributed to the runaway carnage that happens on such nights in rural Indiana. To be sure, I'd already saved countless earthworms from certain doom.

The werewolf followed my car, evidently angry that I'd interrupted its sojourn across U.S. 27 three miles south of Richmond, or a mile west of Boston, a mile east of Abington. Not far from the state TB hospital.

Right in there somewhere.

The creature followed me home and the next day, I saw scratch marks on the hood of my car, marks that were not of this world.

Many years later, to shorten this story, I wrote a novel about that night, mixing in some truth with a tad of embellishment. The real facts are way too frightening to share.

I'd like somebody to buy that book.

It's about Opakwa.

It's a story not for the faint of heart.

Tuesday, February 20, 2018

Up on dry land

Usually, a blog headline has something to do with the body of the whole thing. We learned that back in J-school.

Such as: F**k you!

Now that I have your attention, please read the rest of this.

Which has nothing to do with anything, so I will alert you in advance, this blog item is about dangling modifiers.

Nasty stuff, that.

I have a couple of buds who don't write but are amazed that I do, or can. I actually realized long ago that "you" has three letters in it, and was thus rewarded with a cum laudical degree from the university.

State University.

It came around that somebody asked me how I decided what my story would be about and I said, it's about the absurdity of life. Everything is a joke if it doesn't ruin your carpet or bankrupt you.

Optionally, graveyards are either fun for frolics or something else.

I wrote a story that has been alternately titled Gone With the Wind, Grapes of Wrath or just ... Fairfield. I will come up with something better eventually. I don't want to share much about it but it's a zombie thriller with real live dead zombies that came back to life because they wanted to have fun again.

But it is about graveyards and the peculiar events that can happen in a paranormal story that make the whole process of crossing over a quite human event. That is because it was written by a human.

People are what make stories. It's what they are about and it's who they are intended to reach.

We live in a world now that is lubricated by ridiculous headlines.

Start from the back and work forward. The headline should make sense at that point.

Such as: F**k you!

Now that I have your attention, please read the rest of this.

Which has nothing to do with anything, so I will alert you in advance, this blog item is about dangling modifiers.

Nasty stuff, that.

I have a couple of buds who don't write but are amazed that I do, or can. I actually realized long ago that "you" has three letters in it, and was thus rewarded with a cum laudical degree from the university.

State University.

It came around that somebody asked me how I decided what my story would be about and I said, it's about the absurdity of life. Everything is a joke if it doesn't ruin your carpet or bankrupt you.

Optionally, graveyards are either fun for frolics or something else.

I wrote a story that has been alternately titled Gone With the Wind, Grapes of Wrath or just ... Fairfield. I will come up with something better eventually. I don't want to share much about it but it's a zombie thriller with real live dead zombies that came back to life because they wanted to have fun again.

But it is about graveyards and the peculiar events that can happen in a paranormal story that make the whole process of crossing over a quite human event. That is because it was written by a human.

People are what make stories. It's what they are about and it's who they are intended to reach.

We live in a world now that is lubricated by ridiculous headlines.

Start from the back and work forward. The headline should make sense at that point.

Taking ourselves seriously is probably a mistake

I snipped this list from Authorlink.com that is pretty succinct in what their stable of insiders think of the rest of us:

Traditional publishing may be for you if:

- You have had your book professionally edited

- You have taken the time to search for and land a literary agent who can represent your book to the traditional houses.

- Are willing to take editors’ suggestions for revisions

- Have realistic expectations about how much money you will make

- Have a solid promotional platform, such as a large website, speaking schedule, existing record of book sales or are a known celebrity.

- Are willing to wait for one to two years to see the book in print.

- Are willing to self-promote like crazy, even though a traditional publisher should be doing the job.

- Don’t mind turning over the rights to your book.

Essentially, the website that dedicates itself to writers, agents, publishers and readers has made it clear that we should probably not bother because (No. 5) we just aren't successful enough.

Dunno, but this sort of advice is the reason people publish their own books, which Authorlink is proud to advise us about as well. It's just not as interesting.

Monday, February 19, 2018

Write what you think you know

The adage about writing what we know is always a policy that makes sense. I really don't know much about hiking in the Sahara, but I can say that I'd be accurate in describing it as hot and dry without much chance of getting a ride to the nearest gas station.

Don't run out of gas. I actually did that once, so I can safely write about it with some degree of enthusiasm.

I recall getting my first PC about 20 years ago and snooping around for various websites that discussed writing. Never did I have any illusions about the craft. Writing what one knows is hardly enough if one has no idea how to structure a piece of prose that's more than five or six pages long.

So I wrote a couple of crappy novels, and I pawned them off on an e-book operation that promised me millions in royalty. Clueless, we all were. The E-book industry looked like a comer at the time. I think it missed its window and suffered broken fingers, I think I sold 3 novels.

Anyway, I still have the manuscripts for those classics and don't intend to even read them again. Well, someday ....

The funny part was, I also tripped over a few other things. Then one day, I decided to write a porn novel. No agenda, no plan, no plot ... just included as much profanity, sex and combinations thereof. I just wanted to see if I could write one. I think it took me a week. I offered it to this woman who had an "erotica" website and she took it. I made a couple of hundred dollars off the thing over a dozen years.

I sold a couple of others to a different outfit. The stuff wasn't so much porn as it was just fun stories with people doing sexual things. I called it blue-collar romance, or love stories about people who were considering being in love.

I still have that stuff around here too and have considered recasting it with a little less gravy and a few more potatoes.

But what I learned along the way is that you don't always have to write what you know. What you first need to do is learn how to write. Novels are hard work. The reward is awesome.

It's almost better than getting laid.

Don't run out of gas. I actually did that once, so I can safely write about it with some degree of enthusiasm.

I recall getting my first PC about 20 years ago and snooping around for various websites that discussed writing. Never did I have any illusions about the craft. Writing what one knows is hardly enough if one has no idea how to structure a piece of prose that's more than five or six pages long.

So I wrote a couple of crappy novels, and I pawned them off on an e-book operation that promised me millions in royalty. Clueless, we all were. The E-book industry looked like a comer at the time. I think it missed its window and suffered broken fingers, I think I sold 3 novels.

Anyway, I still have the manuscripts for those classics and don't intend to even read them again. Well, someday ....

The funny part was, I also tripped over a few other things. Then one day, I decided to write a porn novel. No agenda, no plan, no plot ... just included as much profanity, sex and combinations thereof. I just wanted to see if I could write one. I think it took me a week. I offered it to this woman who had an "erotica" website and she took it. I made a couple of hundred dollars off the thing over a dozen years.

I sold a couple of others to a different outfit. The stuff wasn't so much porn as it was just fun stories with people doing sexual things. I called it blue-collar romance, or love stories about people who were considering being in love.

I still have that stuff around here too and have considered recasting it with a little less gravy and a few more potatoes.

But what I learned along the way is that you don't always have to write what you know. What you first need to do is learn how to write. Novels are hard work. The reward is awesome.

It's almost better than getting laid.

How does one write?

Skip over the obvious. We don't have to discuss the barnyard cluck to know how to cook an omelette.

In reconstructing this blog after a long period of dormancy that connected to my former work, which I obviously no longer do, I have tried to remember the reasons one actually DOES a blog. Nobody really ever reads it. Some of my best writing on the Fairfield 200 blog has been noticed by fewer than a dozen people -- and some them ought to actually care what has been written there.

Alas not my problem.

So how does one write?

According to people who try to sell us on the notion that anybody can publish a novel, it's essentially the principle of the primate being given a ream of paper and an IBM Selectric. The Selectric was one ba-dass typewriter, so a chimp would probably adapt fairly well.

I was driving home from work one night in a fog, literally, and was enveloped by the real fear that a werewolf might jump out onto the road. I'd hit the damned thing, just wound it ... and it would come scratching at my door with an agenda. We didn't have a lot of werewolves around town in those days, but some.

Forty years later, I wrote Opakwa.

Nobody has bought that book yet, which is a damned shame.

The fog I experienced the other day was not dissimilar, but the werewolf is in another county now.

I think.

That doesn't say very much about the question: How does one write?

Dunno ... ask the monkey. He probably has an agent.

In reconstructing this blog after a long period of dormancy that connected to my former work, which I obviously no longer do, I have tried to remember the reasons one actually DOES a blog. Nobody really ever reads it. Some of my best writing on the Fairfield 200 blog has been noticed by fewer than a dozen people -- and some them ought to actually care what has been written there.

Alas not my problem.

So how does one write?

According to people who try to sell us on the notion that anybody can publish a novel, it's essentially the principle of the primate being given a ream of paper and an IBM Selectric. The Selectric was one ba-dass typewriter, so a chimp would probably adapt fairly well.

I was driving home from work one night in a fog, literally, and was enveloped by the real fear that a werewolf might jump out onto the road. I'd hit the damned thing, just wound it ... and it would come scratching at my door with an agenda. We didn't have a lot of werewolves around town in those days, but some.

Forty years later, I wrote Opakwa.

Nobody has bought that book yet, which is a damned shame.

The fog I experienced the other day was not dissimilar, but the werewolf is in another county now.

I think.

That doesn't say very much about the question: How does one write?

Dunno ... ask the monkey. He probably has an agent.

The art of being published

It's been said that we are divided into two groups:

Those who divide people into two groups, and those who do not.

At first glance, this requires more thought.

It's deeper than it appears.

There are those of us who are published authors and there are those of us who are encouraged to be so.

The problem is, the traditional process has been scripted for us.

We can't get there from here.

Well, one sort of 'can' get there, but it's like being asked to walk the entire distance while the really great ones among us get to take the airplane.

This includes agents, I reckon.

I recently joined up with Authorlink.com, which is a go-to operation for people looking for agents, publishers, writing tips, advice, and offering a place to strut your stuff.

Basically, the information for people who would rather take the plane than walk was: Forget it, you'll not get a ticket.

I'm not quite that calloused yet. I wrote some stuff and it's good. I won't walk or take the plane but I will be damned if I give it away.

It's sort of a shame that the people who root us on and are in a position to help us succeed are so disinclined to actually follow up on that.

In that respect, I divide people into two groups.

Those who divide people into two groups, and those who do not.

At first glance, this requires more thought.

It's deeper than it appears.

There are those of us who are published authors and there are those of us who are encouraged to be so.

The problem is, the traditional process has been scripted for us.

We can't get there from here.

Well, one sort of 'can' get there, but it's like being asked to walk the entire distance while the really great ones among us get to take the airplane.

This includes agents, I reckon.

I recently joined up with Authorlink.com, which is a go-to operation for people looking for agents, publishers, writing tips, advice, and offering a place to strut your stuff.

Basically, the information for people who would rather take the plane than walk was: Forget it, you'll not get a ticket.

I'm not quite that calloused yet. I wrote some stuff and it's good. I won't walk or take the plane but I will be damned if I give it away.

It's sort of a shame that the people who root us on and are in a position to help us succeed are so disinclined to actually follow up on that.

In that respect, I divide people into two groups.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)